Why does Displaying Broken, Dirty, and Corroded Objects Limit Audience’s Understandings of the Past?

Overall, when objects are dirty, broken, or corroded, important details can be obscured, limiting the information that objects can present in conveying the chosen “truths” of the past. Dirty objects limit the understanding of designs and surface details, causing a different perception of what they were like when in use. Broken objects make it difficult to discern forms and when objects demonstrate heavy layers of corrosion, it is difficult to ascertain the true nature of the original materials, as well as their original forms.

In modern Western society, both “truth” and the artist’s intent are placed in very high esteem when it comes to presenting objects as well as works of art (Caple, 2000: 20). The use of objects in presenting the past is seen as effective in conveying the “truth”, as opposed to historical documentation which is perceived as biased (Caple, 2000: 18, Ulrich and Gaskell, 2015: 3).

When objects are dirty, broken, or corroded, understanding their past form becomes more difficult. The information objects can convey about their past is limited, as elements of the original form, function, and usage may be obscured. Evidence surrounding the history and significance of an object may be shrouded from viewers when the artefact is corroded or broken, thus creating the need to clean objects in order to demonstrate some aspects of their original forms (Podany, 1994: 40).

The Importance of Dirt and Corrosion

In comparison to the over-zealous restoration and cleaning of objects in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, conservators have now realised that producing a pristine object destroys quite a bit of valuable evidence about the past (Corfield, 1988: 261). Soiling layers on artefacts are important in illustrating ways of life in the past in more detail than beautifully “cleaned” counterparts, as more information is gained surrounding their use (ibid). Therefore, preserving traces of damage and dirt become important elements in preserving the “truth” of the past (Caple, 2000: 22).

As conservators become more adept at identifying materials, it is clear that even cleaning the surface of an object may remove evidence of use of the object, which may be considered an important part of its history (Caple, 2000: 93). This idea can be seen with the uniform of a soldier who served at the Somme at the Australian War Memorial Museum (Caple, 2000: 93). This uniform is displayed still caked in the mud of the battlefield. The dirty uniform, compared to a mended or clean one, demonstrates the harsh reality of war, illustrating aspects of the object that are deemed important in presenting the “truth” of its past in context. It is therefore important to thoroughly evaluate all facets of an object before determining the necessary actions taken to preserve its “truth” for the future, as well as the importance of documenting all information about an object and its soiling or corroding layers during the conservation process.

Nevertheless, when objects are presented as dirty or corroded, our perception of the past is altered. Instead of the bright vibrancy of past societies, we are left with markers of age. This limits what “truths” are conveyed about the past, potentially preventing a greater understanding of how people lived and worked throughout history. Dirty artefacts tend to limit the aesthetic elements, centring primarily on the historic. Therefore, these two elements, aesthetic and historic, need to be balanced in order to ensure that a more complete picture of the past can be made apparent, by deciding what should be retained and if objects should be cleaned and/or mended.

The Limitations of Dirty Objects

Dirt and dust obscure the surface of an object from view, making it appear duller and darker (Caple, 2000: 90). The extent to which decorative details and other features can be recognized is also reduced.

Dirty, faded, or incomplete objects and textiles present information that is only comprehensible to a select audience (Brajer, 2009: 26). This limits what the objects can indicate about the past as well as restricting the audience to whom information can be presented thereby obscuring the “truths” of the past, as fewer interpretations imply more bias. Dirt on objects tends to conceal details on the surfaces of objects (CCI, 2007).

Further, information and the “truth” of textiles can be limited due to the disfigurement caused by soiling and creasing (Eastop and Brooks, 1996: 229). Details of embroidery and weaving can be obscured due to the soiling and creasing of tapestries and clothing, limiting what can be determined about production practices in the past (De Boeck et al., 1989: 5). Such soiling can be seen with the Avarice tapestry (Hutchinson, 1989: 90). Levels of dirt left on objects can suggest that they were perhaps of lower value and shows a lack of care. This alters the perception of the past and limits the availability of a viable “truth”.

Overall, it is important to at least remove layers of soiling that do not directly relate to the use of an item; such as the layers of dirt and dust that form whilst buried or in storage, as they limit what objects can convey about the past. Though the layers may be useful in some respects, it is deemed necessary to record and then remove these deposits in order to better understand the object as an aesthetic entity, as well as to understand the form and materials present within it.

The Limitations of Broken Objects

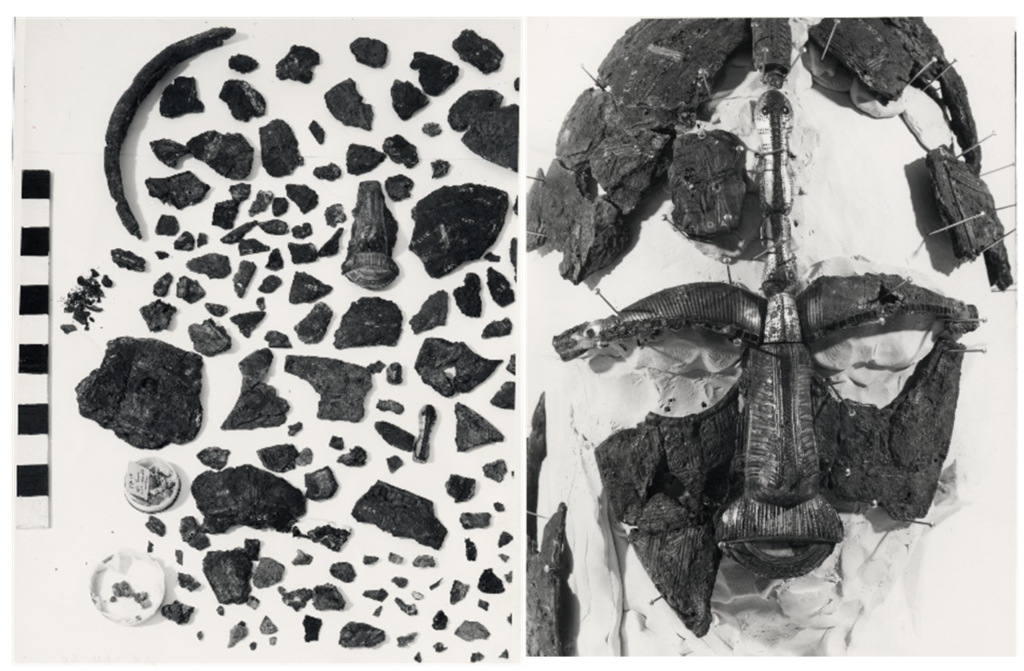

Broken objects are seen as difficult to interpret based on the loss of structural and aesthetical appearances (Ahmed, 2015: 183). If objects are presented in their broken state, it is possible that the perception of the past remains as just a record of broken fragments without the recognition that these objects were once whole. This perception gap limits the information the artefact can convey about certain aspects of the past, such as form and function.

Furthermore, deformed objects are also difficult to interpret without restoration, due to the nature of the original object and its form having been lost (Caple, 2000: 92; Corfield, 1988: 262). The distortion that occurs during burial is incidental to the history of the objects and thus is taken as less important to the “truths” conveyed (Corfield, 1988: 263). Thus, the focus is more on the aesthetic aspects of an object’s truth, as they are more important than its depositional history. The “truths” determined for these artefacts are seen to be attached to their original forms and not the way the objects were discovered, triggering the need to reshape pieces in order to convey more information surrounding the past.

The Limitations of Corroded Objects

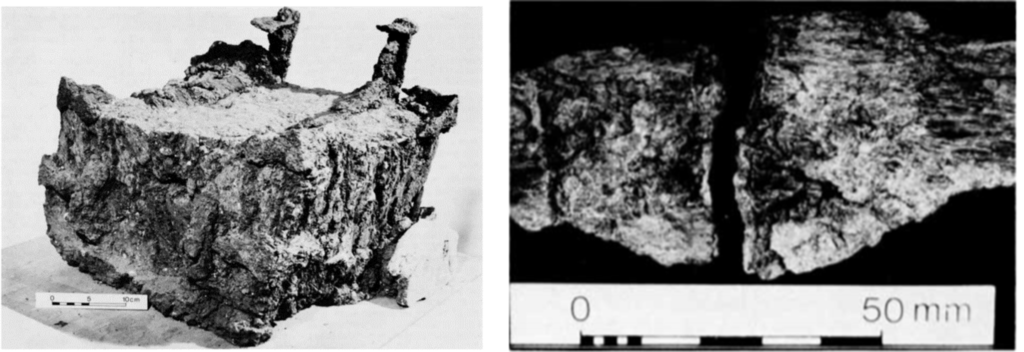

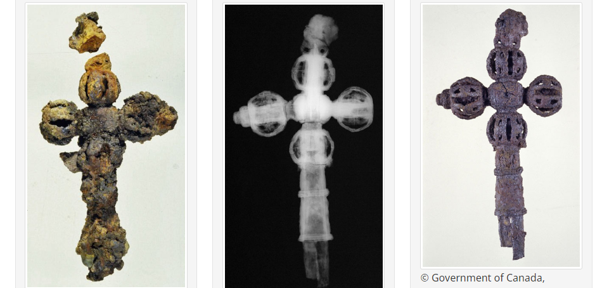

Many archaeological objects have corroded as a result of long periods of burial (Caple, 2000: 92). When objects have corroded, the general shape of objects tends to be visible, but the details of the structure are concealed or lost, limiting the information that can be presented about metal objects of the past (CCI, 2013). A common consequence of corrosion is the disruption of the remaining material within the artefact (English Heritage, 2013: 3). The effects of corrosion vary from a minor surface change to the complete loss of fundamental material, which reduces its ability to convey information about the original forms of objects as well as their composition (ibid, 4). Thus, the removal of corrosion is imperative in understanding the “truths” of the past.

Corrosion can also obscure surfaces and reduce the readability and research potential of objects, as well as impair their aesthetic appeal (English Heritage, 2013: 6). Surface details of objects such as coins are easily hidden by corrosion, making it difficult to decipher the origin of these objects (Viljus and Viljus, 2013: 31).

The Benefits of Presenting Cleaned and Restored Objects

The urge to remove dirt and dust obscuring an object stems from an unconscious assessment that cleanliness represents the correct appearance (Caple, 2000: 22, 90). In conservation, cleaning is described as the removal of soiling and decay products from the surface of an object (ibid, 90). In some cases, however, intensive intervention may be necessary in order to regain or maintain an artefact’s meaning or value (Brooks, 2014b: 384). This tends to be the case when objects are dirty, broken, or corroded.

Cleaning an object may aid in its preservation, reveal the form of the object, and uncover more information about its past (Caple, 2010: 6). This creates the need to intervene, with respect to degradation processes within objects, in order to preserve them for future audiences and research. The acts of restoration and conservation are interpretive, aiming to overcome the decay in order to allow engagement with both the physical and metaphysical aspects of an object (ibid). Thus, conservators have an important role in recreating what is “authentic” in a physical object (Brooks, 2014a: 7).

The reconstruction of broken archaeological objects is important in order to demonstrate both aesthetic and historical aspects of the artefacts (Ahmed, 2015: 183). These reconstructions provide the audience with an understanding of how people lived in the past and who they were, reflecting ideas, beliefs, and activities (NPS, 2006 via Ahmed, 2015: 183). Reconstructions remedy the challenge to incorporate information about the “truth” of the past directly on or with the object, particularly in the case of broken pottery (Podany, 1994: 41).

The extent to which soiling and decay products are removed is a matter of careful judgment on the part of the conservator; balancing the loss of information, which soiling and decay products can contain, against the benefits of revealing the original forms as well as original surfaces of the object to improve its stability (ibid). This balance is considered to be a “Goldilocks point” (Eastop and Brooks, 1996). Conservators have long debated the acceptable degree to which one can intervene on an object, as it is impossible to retain all of the information with the object (Brooks, 2014a: 6). This demonstrates the need for the diligent recording of details throughout the conservation and restoration processes. Currently, it is recognised that if an object is dirty but otherwise stable, no further action is required in order to conserve it (Lavelle and Miller, 2017: 4).

Bibliography

Ahmed, H. (2015). Restoration of Historical Artefacts and Made Available for Exhibition in Museums. Journal of American Science, [online] 1212(55), pp.183–192. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301790418_Restoration_of_Historical_artifacts_and_made_available_for_exhibition_in_museums.

Brajer, I. (2009). Authenticity and restoration of wall paintings: issues of truth and beauty. In: E. Hermens and T. Fiske, eds., Art, Conservation and Authenticities: Material, Concept, Context. Archetype Publications, pp.22–27.

Brooks, M. (2014a). Decay, conservation, and the making of meaning through museum objects. In: Ways of Making and Knowing: The Material Culture of Empirical Knowledge. Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp.377–404.

Brooks, M. (2014b). “Indisputable Authenticity”: Engaging with the real in the Museum. In: Authenticity and replication: the “real thing” in art and conservation. Authenticity and replication: the “real thing” in art and conservation: proceedings of the international conference held at the University of Glasgow, London: Archetype Publications, pp.3–10.

Canadian Conservation Institute (2007). Basic Care of Coins, Medals and Medallic Art. Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) Notes, [online] 9(4). Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/canadian-conservation-institute-notes/care-coins-medals-medallic-art.html.

Canadian Conservation Institute (2013). Tannic acid treatment for rusty iron artifacts, previously published as Tannic Iron Treatment. Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) Notes, [online] 9(5). Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/canadian-conservation-institute-notes/tannic-acid-rusted-iron-artifacts.html.

Caple, C. (2000). Conservation Skills: Judgement, Method and Decision Making. [online] Oxon: Taylor & Francis Group. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/durham/reader.action?docID=1075355.

Corfield, M. (1988). The reshaping of archaeological metal objects: some ethical considerations. Antiquity, 62(235), pp.261–265.

De boeck, J., Vereecken, V. and Reicher, T. (1989). The Conservation of Embroideries at the Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique. In: The Conservation of Tapestries and Embroideries. Meetings at the Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique Brussels, Belgium. California: Getty Conservation Institute, pp.5–10.

Eastop, D. and Brooks, M. (1996). To Clean or not to clean: the value of soils and creases. In: International Council of Museums: ICOM Committee for Conservation. 11th TRIENNIAL MEETING- ICOM COMMITTEE FOR CONSERVATION. London: James & James, pp.687–691.

English Heritage (2013). Guidelines for the Storage and Display of Archaeological Metalworks. Guidelines for the Storage and Display of Archaeological Metalworks.

Hutchison, R. (1989). Gluttony and Avarice: Two Different Approaches. In: The Conservation of Tapestries and Embroideries. Meetings at the Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique Brussels, Belgium. California: Getty Conservation Institute, pp.89–94.

Keepax, C. and Robson, M. (1978). Conservation and Associated Examination of a Roman Chest: Evidence for Woodworking Techniques. The Conservator, 2(1), pp.35–40.

Lavelle, C. and Miller, L. (2017). Successful Basic Interventive Conservation. Successful Guides. [online] Available at: https://www.aim-museums.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/successful-basic-interventive-conservation-2017.pdf.

Newton, C. and Cook, C. (2018). Caring for archaeological collections. Caring for archaeological collections.

Podany, J. (1994). Faked, Flayed or Fractured? Development of Loss Compensation Approaches for Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Objects Specialty Group Postprints, [online] 2, pp.38–56. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/312884/Faked_Flayed_or_Fractured_Development_of_Loss_Compensation_Approaches_for_Antiquities_at_the_J._Paul_Getty_Museum.

The British Museum (n.d.). The Sutton Hoo Helmet. [online] Collections Online at the British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1939-1010-93 [Accessed 9 May 2020].

Ulrich, L. and Gaskell, I. (2015). Tangible things: making history through objects. Oxford; New York; Auckland: Oxford University Press.

Viljus, A. and Viljus, M. (2013). The Conservation of Early Post-Medieval Period Coins Found in Estonia. Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 10(2).

Weiner, N. (2016). Ancient Coins and Looting. [online] Biblical Archaeology Society. Available at: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/archaeology-today/cultural-heritage/ancient-coins-and-looting/ [Accessed 9 May 2020].