How Far do We Take It?

A Discussion on the Ethics of Painting 60-year-old Anatomical Models

Conservation has been described as “the means by which the true nature of an object is preserved” (UKIC, 1990: 8). True nature in this sense refers to the evidence of an object’s origins, its original construction, and the materials of which it was composed, which should ideally be preserved based on the premise that the objects constitute evidence of the past (ibid). In order to preserve this “true nature” of objects, conservators endeavour to promote the concepts of reversibility and minimum intervention.

However, there are cases where there is a struggle between this ethical ideal and the realities of expectations and the use of objects within museums. This is the case with a series of anatomical model skulls I worked on for the Durham University Museum of Archaeology.

The Skulls

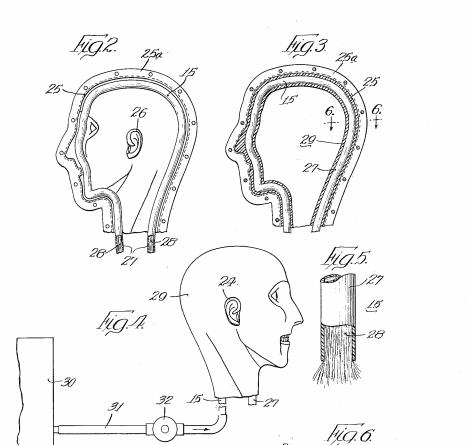

The crania of these anatomical models are hollow pressure cast, as evidenced by the holes at the base of all the skulls (McCormick, 1953). These models were likely made from a mould of a wax or plasticine model of the original skulls (Nemec, 2014). The three mandible pieces are also cast, but as solid plastic.

The surfaces of all the skulls have been painted, likely with a form of acrylic that was sprayed on. This limits the physical characteristics that can be used to help identify the material. The models are likely a thermoplastic, most likely polyvinyl chloride (PVC) but potentially could be polyethylene (PE). This is deduced from the manufacturing style, as the plastic had to be in liquid form to be injected into the mould for hollow casting (Shashoua et al., 2012, McCormick, 1953).

Based on comparative examples of anatomical models found on antiques websites, as well as the history of the Deutsches Hygiene Museum Dresden, for which several of the models have distinct tags, these models were likely manufactured in the 1960’s (Davidowski).

These models were intended to be used for teaching purposes, to clearly demonstrate the anatomy of early hominids in comparison to two-dimensional drawings, as visual instruction through exhibition grew more common (Nemec, 2014, Koslow, 2020). These models were intended to “simplify” the complex, scientific notions of anatomy and history to drive popular education and understanding (Koslow, 2020).

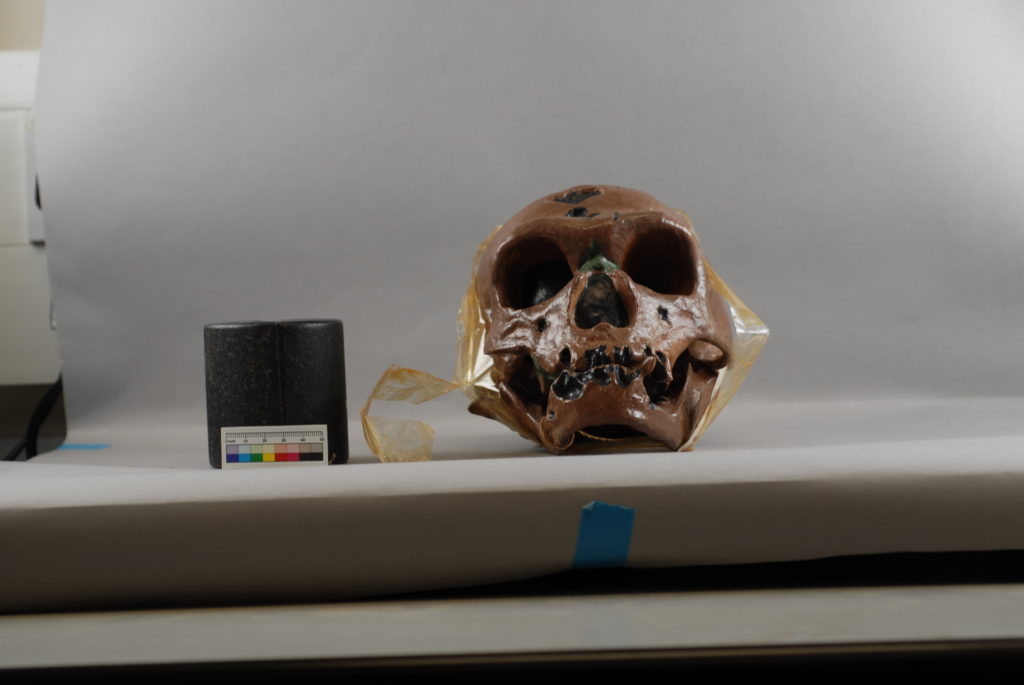

However, there is no information surrounding the strange colouring of the models, specifically the Cro Magnon and La Chapelle skulls. All the hominid models from the museum are represented in their own distinct colours, likely used to denote each type of remains from others. Within the models themselves, it is likely that the stark green colouring in areas of the La Chapelle skull was used to distinguish areas of delamination and loss in the original remains (see below). The green colour for these areas of delamination can be seen in other models of the same type from the Deutsches Hygiene Museum Dresden, but it is unclear why this colour was specifically chosen. It remains uncertain why Cro Magnon was painted a decidedly unnatural colour.

Treatment

The value of these skulls lies primarily with their use as teaching aids, allowing audiences to better understand the physiology of human ancestors and experience the remains in a 3-dimensional form on a wider scale than the original remains.

The aims in conserving these anatomical models included the removal of all tape and residues from the skulls, as they could damage the plastic and were extremely unsightly (American Institute of Conservation, 2021). Following this, any soiling was removed to protect the skulls from further deterioration, as well as remove distracting discolouration from surfaces.

It was also determined that the Cro Magnon, Rhodesier, and La Chapelle models required repainting in order to go on display, as the original colouring of these skulls was considered distracting and “alien-esque” (Armstrong, pers. comms.). This would limit the usefulness of the models as teaching aids, as they would not be as easily recognised as human ancestors due to their colouration.

Unfortunately, the notion of repainting these models raises serious ethical questions. Though these models are primarily meant to be used as anatomical models for teaching, they are still historical objects, being over sixty years old. Repainting these objects would remove a part of their history. The process has limited reversibility, as attempting to remove modern paint will likely also remove the original paint layers and damage the plastic.

So how can the loss of this information be balanced with the needs of the museum? There has been an ethical struggle between historical and aesthetic restoration, particularly in the art world, for decades. Conservators are constantly attempting to keep a balance between retaining historical information presented by an object, and the aesthetics that the artist intended and that audiences expect.

With the skulls, the aesthetic and teaching surfaces were deemed to outweigh the possible historical significance of the original colours of the models. Thus, per the museum’s request, the La Chapelle and Cro Magnon models were airbrushed with acrylic paint in order to present a “natural” bone-like colour. This would hopefully allow audiences to recognise the skulls as those of hominin ancestors.

To mediate the losses this process would entail, the models were properly photographed and recorded. Furthermore, all original tags and labels were kept in situ and clean to ensure their manufacturing information and historical ties to the Deutsches Hygiene Museum. The “x19_” labels (based on the labels of each skull) to the top of each cranium were also retained or re-added. This allowed for a reasonable balance between the museum’s expectations of the objects as educational pieces and their historical significance.

Conclusion

“All actions of the conservator must be governed by a respect for the integrity of the property, including physical, historical, conceptual, and aesthetic considerations” (IIC-CG and CAPC, 1989. 5) However, many conservators believe that this integrity is a matter of interpretation rather than of attributes that are integral to the object.

Since these anatomical models were designed for a specific purpose, it can be argued that the repainting of these skulls was warranted. It allowed more accuracy within their interpretation and increased their educational value. Furthermore, without knowing the reasoning behind the decision to use unnatural colours, it is hard to insist on the importance of retaining this element. Despite this, it does remove an element of their history, as the models will more than likely never return to their previous colouration, which will only be realised through their documentation.

If you’d like to read the full treatment report of the Anatomical Hominin Models, please click here.

What are your thoughts? Which aspects of the objects should be highlighted over others? Let me know!

Works Cited

American Institute of Conservation (2021). Tape Removal. [online] www.conservation-wiki.com. Available at: https://www.conservation-wiki.com/wiki/Tape_removal [Accessed 14 Jun. 2021].

Davidowski (n.d.). Anatomical Teaching ‘Skull’ Model. [online] Davidowski. Available at: https://www.davidowski.nl/collections/objects/scientifics-and-biology/anatomical-teaching-skull-model-made-from-plaster-and-plastic-germany-1960s-deutsches-hygiene-museum-dresden-small-damages-and-repairs-but-overall-great-shape-size-w-6-x-h-5-x-d-9-inch-mid-20th-century-1625875 [Accessed 15 Jun. 2021].

International Institute of Conservation (n.d.). Conservation and Ethics | International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. [online] www.iiconservation.org. Available at: https://www.iiconservation.org/content/conservation-and-ethics [Accessed 28 Apr. 2022].

Koslow, J. (2020). Exhibiting Health: Public Health Displays in the Progressive Era. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

McCormick, J. (1953). Plastic Molded Anatomical Model and Method of Molding Plastic Articles. [online] Available at: https://patents.google.com/patent/US2763070A/en [Accessed 2 Sep. 2021].

Nemec, B. (2014). Modelling the Human – Modelling Society Anatomical Models in Early Twentieth-Century Vienna and the Politics of Visual Cultures. Histoire, Médecine Et Santé, (5), pp.61–76.

Shoshoua, Y., Fournier, A., Martin, G. and Lavedrine, B. (2012). Preservation of Plastic Artefacts in Museum Collections. Paris: Comité Des Travaux Historiques Et Scientifiques.

Smithsonian Institution (2010). La Chapelle-aux-Saints. [online] The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program. Available at: https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/la-chapelle-aux-saints.