Caring for Collections during Conflict

Disclaimer: the bulk of this information was collected prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine (February 2022) and thus does not delve into the extent of work performed to protect Ukrainian cultural heritage. Please refer to the links under “Additional Information” for current efforts in this region.

Conflict is a risk for all cultural heritage and museum collections in particular. Where natural disasters tend to inflict rather specific types of damage to collections, there is no particular type of damage associated with conflict (Teijgeler, 2006). Instead, the impact of conflict on museums can resemble the effects of any combination of natural disasters as well as put collections at risk for physical damage in relation to looting and defacement (ibid).

The 1954 Hague Convention provides a legal benchmark in order to limit deliberate military attacks on cultural heritage sites and museums (Daniels and Wegener, 2016). However, this does not protect museums and other heritage sites from becoming collateral damage of conflict (fig. 1), or from looting and vandalism (fig. 2) (Hayashi, 2015). In these scenarios, it is primarily up to local heritage professionals to protect museum collections (Daniels and Wegener, 2016). Most procedures are part of normal collections management and are mirrored in natural disaster mitigation by museum professionals. Professionals continue to learn new strategies that help determine the course of collections management during times of conflict. ICCROM and the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative have created a handbook and a toolkit regarding salvage planning for areas in crisis which can help strengthen disaster planning efforts (https://culturalrescue.si.edu/resources/).

This blog will focus solely on object security during conflict. However, emergency planning and documentation are also essential for the proper safeguarding of collections during a crisis.

In any museum, security measures should be taken in order to protect collections from theft or vandalism (ASIS International, 2006). The most common security measure involved in most emergency preparedness strategies is the complete shutdown of a museum (Teijgeler, 2006). This procedure prevents personnel and visitor casualties more than safeguards collections, but the safety of human beings must always be put before that of the collections (ibid). Once a museum is closed, there are several options to secure collections, depending on the risks and time necessary to proceed. One option is to move part of the collections to safer premises outside the institution, or even outside the country (Dorge and Jones, 1999; Teijgeler, 2006). This, of course, takes a considerable amount of time and resources to achieve, stressing the importance of solid planning prior to a crisis. Another option is to secure the museum itself, attempting to barricade out vandals and looters, whilst stabilising objects in situ in case of physical harm to the structure. The decision to move objects to safe havens as opposed to leaving them in their institution must be taken on a case-by-case basis, as both demonstrate possible risks to collections.

Safe Havens

Creating safe havens for collections involves moving collections to a more secure location within the country or sending them abroad to ensure their protection (AAMD, 2015).

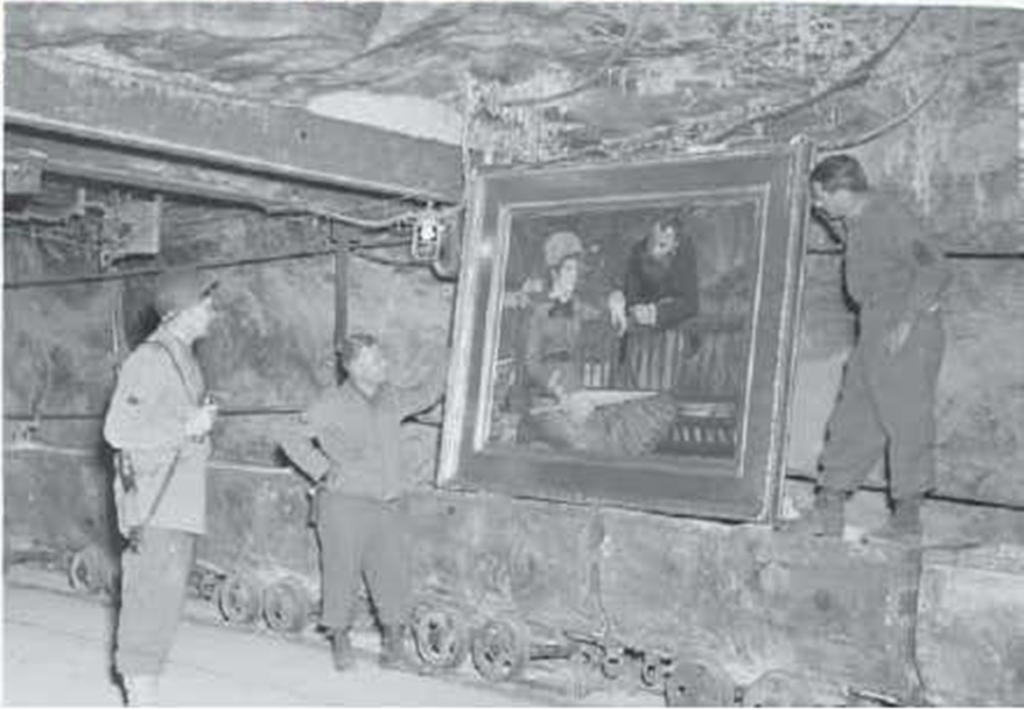

Moving collections to secure locations within the same country is a common process during times of conflict (fig. 3). The National Museum of Lebanon moved much of its precious metal objects to the vaults of the Central Bank for safekeeping, whilst other objects were placed in underground chambers of a crusader castle in Byblos during the civil war (Erlich, 2003 via Teijgeler, 2006). More recently, historic manuscripts from Timbuktu, Mali were evacuated in 2012 to the capital Bamako, saving them from extremists who burned the contents of Timbuktu’s library shortly after (Daniels and Wegener, 2016). Furthermore, in August 2012, the department of antiquities in Syria transported Syria’s archaeological treasures to the National Museum and other facilities, dividing up collections to limit risks (Harkin, 2016).

The movement of objects outside of a country for safekeeping during conflict is less common. The U.K. sent a Magna Carta to the U.S. during World War II, the National Museum of Lebanon sent small and precious objects to the French Archaeological Institute of Damascus, which were returned after the civil war, and collections from Afghanistan were sent to Switzerland in the 1990s, establishing the Afghanistan Museum-in-Exile in Bern (Daniels and Wegener, 2016; Teijgeler, 2006).

Unfortunately, transporting collections during times of conflict is risky, as it can expose them to fragmentation and theft (Daniels and Wegener, 2016). Care must be taken in moving material to a safe haven without further endangering collections. Furthermore, the personnel and time required to dismantle and store collections are intense, and extreme prior planning needs to be taken if there are intentions to send objects abroad (Youkhanna and Gibson, 2008). It is likely that attempting this task is not feasible for many museums in areas of conflict but should still be considered as an option in order to protect collections from looting and vandalism.

In Situ

Protecting collections in situ tends to be a decision made when there is limited time, or when objects cannot be physically moved, but collections must still be protected. In the Iraq Museum, larger objects were left in place, with foam rubber pads placed around the area in order to protect them if they fell (Teijgeler, 2006). Museum staff also blocked the front doors of the museum with cement slabs and sandbagged areas to help protect against blasts (Lee Reilly, 2018). These methods allowed for some protections of the collections. Another security measure, employed by staff after the Museum was looted for several days, was the use of signage stating that the museum was under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army (ibid). This bluff helped stop the looting. Since these looting incidents, special steps have been taken to protect the museum from further attempts without the use of guards. New electronic devices were installed that help control the entrances to the museum, connected to emergency generators in order to ensure the continuous protection of collections (Gibson and Youkhanna, 2008). Staff also constructed additional secure storage for collections and closed a number of entrances to storage areas (ibid).

Other examples of in situ collections security include the use of sandbags and barricades at the Aleppo Museum (fig. 5) and the use of concrete to surround sarcophagi and mosaics in Beirut during the civil war (fig. 6) (Kanjou, 2014). Whilst these procedures are not ideal, they did help protect collections from vandalism and looting.

Whether it is decided to move collections or to keep them in the institution, it is important that storage is kept in good order (Norman, 2000). This can be achieved by keeping objects packed, rolled, or boxed, so they can be moved safely and quickly. Objects on display should have crates, boxes, or rollers prepared even whilst in exhibits, with clear labels and photographs to simplify their packing (ibid).

Conclusion

In the modern era, situations develop very quickly, causing it to be challenging to identify when cultural heritage may be at risk due to political instability and international conflict. Some experts believe that a post-crisis response is more effective than attempts to secure collections pre-crisis (Ferraro and Henderson, 2011), and this has been demonstrated in numerous areas of conflict, particularly in Afghanistan (Perini, 2014). However, many experts also acknowledge the need for procedures for saving cultural heritage during conflict, and that the more time that elapses after an incident, the more irreparable the losses (ibid).

Additional Information:

The Oath of Cyriac

- https://theoathofcyriac.com/

- A docudrama telling the story of protecting collections at the Aleppo National Museum

Culture in Crisis by Smithsonian Institute Sidedoor podcast

- https://folklife.si.edu/news-and-events/saving-ukrainian-cultural-heritage-war

- The contributions of the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (Smithsonian) to salvage efforts in Haiti and how this was applied in Ukraine

- Discussion on the implementation of the 1954 Hague Convention in Iraq and the aims for tracking the deliberate destruction of heritage sites in Ukraine

For more information on damaged cultural sites in Ukraine verified by UNESCO:

- https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/damaged-cultural-sites-ukraine-verified-unesco

- Information regarding known damaged cultural heritage sites/museums in Ukraine (24/02/2022 – 12/12/2022)

Works Cited:

AAMD (2015) AAMD Protocols for Safe Havens for Works of Cultural Significance from Countries in Crisis. [Online]. October 2015. Association of Art Museum Directors. Available at: https://aamd.org/document/aamd-protocols-for-safe-havens-for-works-of-cultural-significance-from-countries-in-crisis (Accessed: 28 April 2021).

ASIS International (2006) Suggested Practices for Museum Security. [Online]. ASIS International. Available at: http://securitycommittee.org/securitycommittee/Guidelines_and_Standards_files/SuggestedPracticesRev06.pdf.

Daniels, B. and Wegener, C. (2016) Heritage at Risk: Safeguarding Museums during Conflict. Museum Magazine. [Online] 27–31. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/27185308/Heritage_at_Risk_Safeguarding_Museums_During_Conflict.

Dorge, V. and Jones, S. (1999) Building an Emergency Plan: Guide for Museums & Cultural Institutions. [Online]. Los Angeles, CA, Getty Conservation Institute. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/emergency_english.

Ferraro, J. and Henderson, J. (2011) Identifying Features of Effective Emergency Response Plans. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. [Online] 50 (1), 35–48. Available at: doi:10.1179/019713611804488946.

Gauch, S. (2014) Triage for Treasures after a Bomb Blast. The New York Times. [Online] 31 January. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/01/arts/design/sorting-through-the-rubble-of-museum-of-islamic-art-in-cairo.html?_r=0 (Accessed: 30 April 2021).

Gibson, M. and Youkhanna, D.G. (2008) Preparations at the Iraq Museum in the Lead-Up to War. In: Antiquities under Siege: Cultural Heritage Protection after the Iraq War. Lanham, Md, Altamira Press.

Harkin, J. (2016) The Race to save Syria’s Archaeological Treasures. [Online]. March 2016. Smithsonian Magazine. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/race-save-syrias-archaeological-treasures-180958097/?no-ist (Accessed: 28 April 2021).

Hayashi, N. (2015) Heritage and Conflict Situations. Museum International. [Online] 67 (1-4), 55–63. Available at: doi:10.1111/muse.12088 (Accessed: 26 December 2020).

Kanjou, Y. (2014) Protection Strategies and the National Museum of Aleppo in Times of Conflict. In: Collections at Risk: Sustainable Strategies for Managing near Eastern Archaeological Collections. 2014 pp. 465–475.

Lee Reilly, J. (2018) Human Rights and Cultural Heritage: Protecting Museum Professionals during Armed Conflict. Thesis. Seton Hall University.

Norman, K. (2000) The Retrieval of Kuwait National Museum’s Collections from Iraq: An Assessment of the Operation and Lessons Learned. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. [Online] 39 (1), 135. Available at: doi:10.2307/3179970 (Accessed: 3 October 2019).

Perini, S. (2014) Syrian Cultural Heritage in Danger: A Database for the National Museum of Aleppo. In: Collections at Risk: Sustainable Strategies for Managing near Eastern Archaeological Collections. 2014 pp. 521–531.

Teijgeler, R. (2006) Preserving Cultural Heritage in Times of Conflict. In: Preservation Management for Libraries, Archives and Museums. London, Facet Pub.

Westcott, T. (2017) Mosul’s Desecrated museum: “IS Smashed up Our history.” [Online]. 14 March 2017. Middle East Eye. Available at: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/mosuls-desecrated-museum-smashed-our-history (Accessed: 30 April 2021).